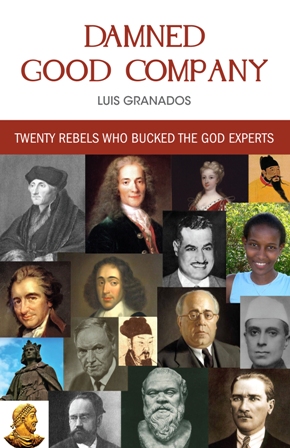

Damned Good Company

by Luis Granados, 382 pages

Humanist Press, ©2012

In Damned Good Company, part-time historian and religion student Luis Granados takes readers across continents and centuries to find fascinating tales of fellow humans who bucked the religious trends of their day.

.Each of the copiously annotated twenty chapters in the book is set up as a rebel-versus-religious case. There are the more famous examples - such as Clarence Darrow vs. Wlliam Jennings Bryan and Thomas Paine vs. Talleyrand - but there are also many less well-known stories here. In some chapter, Granados pits the rebel not against another human, but a group of humans (“Voltaire vs. the Jesuits”) and sometimes the rebel is even at odds with a non-human (such as Chapter 16, “Caroline vs. Smallpox”). And in at least one chapter, the opposing sides aren’t really in opposition at all; Granados begins Chapter 17, “Nehru vs. Gandhi,” by admitting, “Most of the conflicts in this book are between people who loathed one another...Not so with Jawaharlal Nehru and Mohandas Gandhi. Not only did they struggle together for a common goal, but they had a deep bond of affection” (page 297).

But that’s okay for this book; a book, Granados states in his introduction, that’s “about people, not about God” (1). He thus aspires, instead, to tell readers stories of people who stood up and defied those who used their religious beliefs to justify their policies and actions. Not all the rebels are atheists, of course, they are just people who understood reason and logic were better means for living or governing than faith in a deity.

Notable, memorable stories include those of Queen Caroline, who turned down the opportunity to become Empress of Austria because it came with the caveat of converting to Catholicism and then went on to defy the Vatican when she inoculated her family against smallpox. This led to widespread acceptance of vaccination in protestant Europe. Of equal interest is a chapters on Gamal Nasser, who struggled to bring Egypt from the backwards theocracy it was to more modern, enlightened sensibilities. HIs efforts are juxtaposed with his contemporary, David Ben-Guiron, who was leveraging sympathy for the Holocaust to carve out a Jewish theology by unleashing “a campaign of sabotage and murder, in cooperation with Jewish bomb squads” (321). The only chapter that doesn’t seem to fit is the final one, in which Granados relates the highlights of AyaanHirsi Ali’s life with those of President Obama’s. The connection between these two, unlike all the other pairings in the book, is a tenuous stretch.

Each chapter concludes with a gray box containing a question designed to provoke more thinking about the story just concluded. The boxes direct readers to the website discuss.humanistpress. com/categories/damned-good-company. A quick review of the site shows the questions have been pasted word-for-word onto the page (including the wording inviting people to visit the site!) and, as of this writing, there are no responses to any question.

Regardless, Granados writes a sweeping book filled with appealing tales of charismatic characters who fought for reason. I suggest you buy a copy and take a look for yourself.