By Eric Jayne

By Eric JayneMost of us know that Jehovah’s Witnesses are notorious for going door-to-door hocking their religion. They’re kind of like Girl Scouts except the former sells an intangible dubious product that exploits fear while the latter offers delicious chocolate-covered Tagalongs and Thin Mints that exploit your sweet tooth. When it comes to the Jehovah’s Witnesses most of us either say “no thanks” or skip the nominal pleasantry and opt to simply close the door in the middle of their spiel.

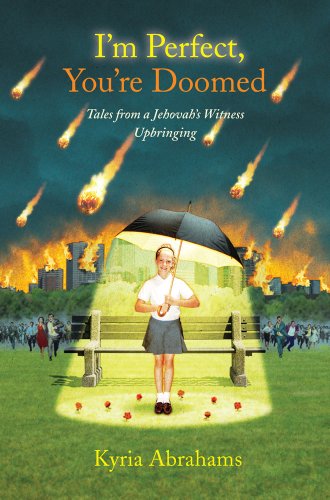

If you’ve ever wanted to know more about the motivation of these door-to-door doctrine peddlers and the culture within the Jehovah’s Witness community, Kyria Abrahams offers an unabashed memoir of her journey from devoted member to disfellowshipped apostate. Currently a stand-up comedian, Abrahams delivers plenty of wit and genuinely humorous anecdotes of her experiences. As the book progresses, however, it takes on a very serious and dark tone riddled with self destructiveness.

The reader is first introduced to a young, eight-year-old Kyria Abrahams who performs a skit with another Jehovah’s Witness in front of their congregation. Abrahams explains that since they were both female they were not allowed to speak directly to the congregation (as that would put them both in a position of authority; one of many Jehovah no-no’s). According to Abrahams, performance skits are commonly employed by female members so that they are able to participate in discussions and idea exchanges in a non-authoritative manner.

As Abrahams leads the reader through her childhood years she explains that many worldly (which means virtually anything unrelated to the worship of Jehovah) inanimate objects are not only thought to be absent of Jehovah but often times possessed by demons. In fact it wasn’t a loveless marriage or financial hardship that caused one of the many moments of familial conflict in the Abrahams’ home. Instead, it was caused by supposedly demonically possessed dinnerware that had been purchased at a flea market. You’ll have to read the book to learn about the fate of the innocent dinnerware.

Abrahams also explains that it wasn’t just saucers and mugs that serve as demonic portals. In the minds of Jehovah’s Witnesses, some Saturday morning cartoons like the Smurfs might have your little tyke capable of singing Ozzy Osborne songs backwards and revealing satanic commands.

As Abrahams grew older she started to develop skepticism. For example, after attending a worldly friend’s birthday party she questioned why birthday celebrations were banned by her religion. Unfortunately, at that point Abrahams was still firmly shackled to the Witness doctrine and carried her beliefs into adulthood. This is where Abrahams’ memoir makes a transformation from funny to disturbing. Without giving away too much away, I found many similarities between Abrahams’ dissenting journey out of Jehovah’s Witness and Ayan Hirsi Ali’s account (Infidel) of her incredible dissent from Islam.

If you’re looking for an introduction or reference guide to Jehovah’s Witness, this book is not going to help you much. Abrahams does a good job briefly explaining the basic rules and terms within the Jehovah’s Witness faith, but the strength really lies in her witty and biting recount of her religious environment blended with difficult psychological issues that were only exacerbated by indoctrination.